If the news about tariffs makes your head spin with all the possible short- and long-term chain reactions—who might have to pay, who might benefit, and who might lose jobs—come spend time in this musical festival analogy with us.

Imagine you’re at Glastopia where several of your favorite bands are playing over the next few days. You’re hungry and ready to order a burger en route to the main stage. You notice an unexpected $5 surcharge as you near the first burger truck — turns out, that extra charge is a tariff on certain food trucks in Glastopia being passed on to you.

Joining us from LinkedIn? Skip further below for our tiny pocket guide to tariffs!

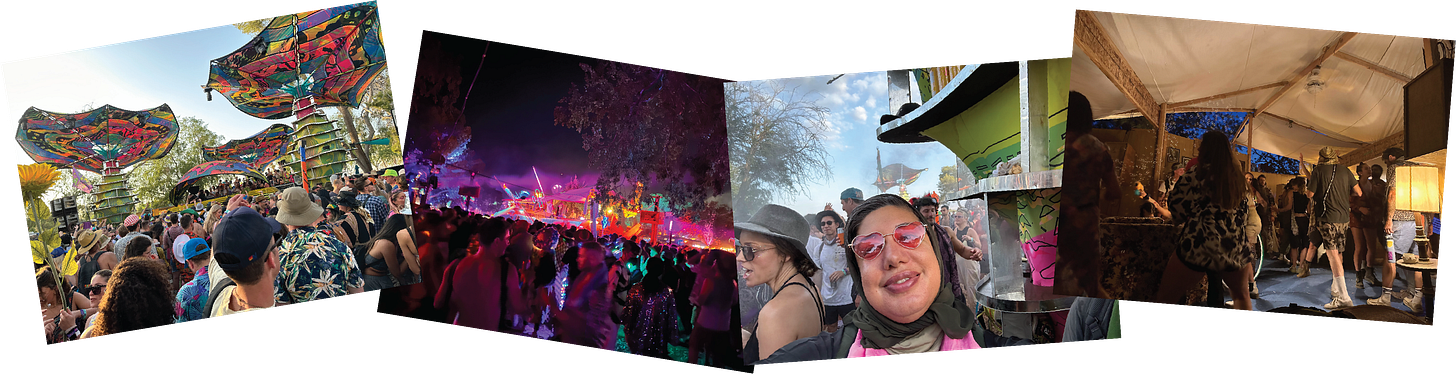

This post is another illustrated companion guide expanding on our conversation from the “It’s Economic!” edition of Volala: Volatility is the Life of Our Party podcast. Immerse yourself in a real-world example of how unexpected fees at a music festival compare to tariffs on imported goods.

1. Tariffs on Imports = Food Stands Slapped with Fees

What do you think happens next? How do you and other festivalgoers respond and what will the food stands do?

You’re probably wondering: How much do stands cut into their profit and how much do they pass on to customers? It depends on how competitive their market is… the more stands that sell burgers, the lower their profit margins pre-surcharge, so the less they can afford to discount prices to offset the surcharge. That means in competitive markets, more or all of the $5 surcharge is passed on to consumers. If a market isn’t competitive (monopoly or only a few sellers) AND buyers are willing to walk away if prices jump, then sellers will have to cut prices more significantly.

2. The Ripple Effect: Supply Chain Jams Up

Who benefits here? Who faces higher costs? Are those costs purely monetary?

Faced with higher costs, businesses and consumers change their behavior, setting off a chain reaction that touches supply chains, prices, and economic growth… and the productivity of the festival as measured in blissed-out minutes for you and other festivalgoers.

While pizza vendors rake in more revenue ($4 per pizza), attendees end up paying surcharges ($5 per burger) or higher costs ($4 per pizza) totaling as much or more than the extra bank vendors made. Also, they pay the cost of longer waits in line and many show up late to the performances they planned to attend, some still with empty stomachs. This makes the concert experience less worthwhile, so some attendees might not pay as much to attend the next festival (lower tax base). And some burger vendors might decide to skip the next festival, too (companies shut down). Meanwhile, there’s discussion of how long the situation will last and whether there’s an opportunity for more pizza vendors to enter the scene.

3. Inflation Creeps Into Unexpected Places

For perspective, let’s apply tariffs to other familiar scenarios. Take cars–if tariffs make imported cars more expensive, fewer people will buy them. Car dealerships might then increase prices on repairs and financing to offset lower sales. So, say you only need a tire change: it might cost more because the dealership is making up for lost revenue.

Or let’s say a tariff is placed on imported beef. Even if you never eat beef, you might still notice higher chicken prices (because more people switch from beef to poultry), more expensive fast food meals (because restaurants adjust overall pricing), or inflation in unrelated grocery items (because supply chains overlap). In some cases, all three of these scenarios might happen.

4. Adjustment Costs: Switching Isn’t Always Free (Or Cheaper)

Just as pizza vendors at the festival had to adjust, businesses across industries respond to tariffs in ways that ultimately make everyday goods more expensive. As we consider the tariffs discussed at the time we recorded this episode (Mexico, Canada, and China), if first-round tariffs are fully implemented, economists expect U.S. GDP to drop by 0.8%*, reducing consumer purchasing power and slowing economic growth.

When tariffs hit, businesses downstream often try to avoid paying the tax on imports by shifting to suppliers in untaxed regions. But switching suppliers takes time — it disrupts existing supply chains, creates delays, and increases production costs. Some companies partially absorb those extra costs, reducing their profits and margins, bringing them closer to going out of business. Others cut their expenses, via layoffs or cost-cutting measures like using cheaper materials, for example. But the most common response is passing costs to consumers, pushing prices higher and driving inflation.

Beyond higher prices, tariffs also lead to other supply chain disruptions. Many businesses delay imports, hoping tariffs will change. When those goods eventually arrive, it creates bottlenecks—too much supply flooding in at once, overwhelming distribution networks, and causing shortages elsewhere. We saw a version of this bottleneck in October 2020 when there was a whopping queue of 109 ships waiting to unload at the Port of Los Angeles. Meanwhile, some countries retaliate with tariffs of their own, making U.S. goods more expensive abroad and reducing demand for American exports.

These are all examples of adjustment costs facing businesses and consumers.

Tariffs also impact monetary policy. Imagine festival organizers require you to buy FestCoins you can spend on food at the festival instead of using dollars. If the food surcharge starts partway through the festival causing prices to rise, everyone will look at their FestCoin stashes and think gosh, I need more FestCoin to buy all the food I thought I could afford (inflation). They’ll offer each other more dollars to buy FestCoin from each other (strengthening FestCoin demand and weakening the dollar). If festival organizers let attendees purchase more FestCoin, they could now charge more dollars because of this stronger demand for FestCoin from their captive audience. Compared to buying a McDonald’s burger outside of the festival, exporting a Bun Jovi meal out of the festival is much less appealing now than before the surcharges, no matter how much your friend who couldn’t come for the weekend wants you to buy them one. (Cold burgers are never as good anyways!)

Just like what happens to FestCoin, tariffs on imports to the U.S. strengthen the U.S. dollar against outside currencies. This makes American exports more expensive and less competitive globally, which is bad for American companies who rely on overseas customers, who in turn face steeper prices and buy less. For U.S. companies that rely on importing components from overseas, the stronger dollar could make their production costs cheaper, but only as long as retaliatory tariffs aren’t placed on those goods. For companies who are in both categories, the math is hard (the economist word for this is “highly non-linear”) and they feel confused, so they either wait and see (holding off on investment) or hustle to put plan As and Bs in place (costly backup supply chains, plans to cut workers and production).

If U.S. prices rise due to tariffs (inflation), investors in the U.S. and other bond markets may demand higher interest rates to offset that extra inflation, further strengthening the dollar. While the Federal Reserve doesn’t typically react to tariffs directly, if inflation rises from all these supply shortages and rising prices, it could keep interest rates higher for longer (fewer rate cuts throughout the year). The exception is if tariffs are so bad they cause the economy to slow or trigger harsh retaliation from other countries that causes a recession — in this worst-scenario case, the dollar could weaken and the Fed could eventually cut rates to soften the impact.

The real impact of tariffs isn’t just an extra charge at checkout. It’s a domino effect that spreads through supply chains, consumer prices, business profits, and even government policy. Just like at the festival, what starts as a price increase on one item can spiral into a broader economic shift, affecting businesses and consumers, far beyond the $5 cost per burger. It affects the productivity of their investment in the festival. With all this readjustment, we’ve not had much time to spend on the music, right?

What are some situations where tariffs make sense as an effective policy?

Imagine there’s a food stand that creates an outsized amount of litter that festival goers and organizers have to clean up. A surcharge can be effective here to spread the cost of cleaning up on those who benefit from the stand. In the real world, this corresponds to putting tariffs on imported goods that pollute or cause other direct harms to society.

A surcharge could also be effective if the electronic music festival organizers want to cultivate food stands that won’t just disappear when a competing rock festival happens the same weekend. Let’s say the government wants to ensure the country has a strong steel industry because it’s critical to national security. A commitment to domestic steel companies can help grow and strengthen businesses, but this is a process that is only effective if the government can guarantee long-term policies and tariffs so companies and their investors and customers know they can bank on that protection as they invest in building factories and supply chains and relationships over many years. For this to happen, tariffs need to be convincingly presented as here to stay, and not as bargaining chips for negotiation.

Some key details here:

Tariffs raise prices when they hit. Only if they are so harsh they make the economy contract (recession from reduced demand) can they eventually cause prices to fall in the long term.

When tariffs hit, as people and investors try to figure out what to expect, there are adjustment costs and frustration can ensue–this is especially true when the tariff duration isn’t announced or credible. People and businesses might feel paralyzed and scared to invest in affected sectors until it’s clear how things will play out, causing economic stagnation.

And those special factors we mentioned above which can result in tariffs paying for tax cuts that leave consumers better off? These are the conditions that must all be met — otherwise, the government can’t raise enough money from tariffs to compensate consumers (via tax cut) for the higher prices they end up paying under the tariff:

Tariffs are stable (ie. adjustment costs are foreseeable and low) AND

the goods being tariffed are coming from very concentrated (not competitive) markets with high-profit margins so those vendors can drop prices to make up for most of the tariff and stay in business AND

Demand for the goods being tariffed is very price-sensitive, forcing the tariffed suppliers to drop margins.

And that concludes this lesson music festival. We’d love to hear your thoughts ahead of the next one! Are there factors related to tariffs that you think we missed? Add them in the comments below:

Every post on the Volala Substack comes with its own party music. Let’s close this one out with something apropos. Here’s “Waiting Room” by Fugazi which was first recorded in 1987 before Guy Picciotto officially left Rites of Spring to join the band. Brendan Canty had just gotten over uncertainty about whether there was a band in his future and booked the group’s first show at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. They didn’t have a name yet, so MacKaye chose the word “fugazi” an acronym among Vietnam vets for “F—-ed Up, Got Ambushed, Zipped In [into a body bag]”. McKay later described he’s singing about the ennui of “waiting for the right people at the right moment.” Way to build your own party in times of uncertainty!

* Sources & Further Reading: